A new class of antibiotics has been discovered 2016. Just by analysing

the bacterial warfare taking place up people's noses. As any technician could say how has this been over look, in health nutrition.

Tests reported in the Journal of Nature found the resulting drug, lugdunin', could treat MRSA infection. The researchers, at the University

of Tubingen in Germany, say the human body is an untapped source of new drugs.

The last new class of the drugs to reach patients was discovered in the 1980s.

Nearly all antibiotics were discovered in soil bacteria, but the University of

Tubingen research team turned to the battlefield, to put on a microscopic level

a struggle. This space for food is taking place between rival species of

bacteria. One of the weapons they have long

been suspected of using is antibiotics. Among the bugs that like to invade the

nose is Staphylococcus aureus, including the dreaded super-bug strain MRSA. It

is found in the noses of 30% of people. About 30% of humans carry this

Staphylococcus.

Tests reported in the Journal of Nature found the resulting drug, lugdunin', could treat MRSA infection. The researchers, at the University

of Tubingen in Germany, say the human body is an untapped source of new drugs.

The last new class of the drugs to reach patients was discovered in the 1980s.

Nearly all antibiotics were discovered in soil bacteria, but the University of

Tubingen research team turned to the battlefield, to put on a microscopic level

a struggle. This space for food is taking place between rival species of

bacteria. One of the weapons they have long

been suspected of using is antibiotics. Among the bugs that like to invade the

nose is Staphylococcus aureus, including the dreaded super-bug strain MRSA. It

is found in the noses of 30% of people. About 30% of humans carry this

Staphylococcus.

Tests reported in the Journal of Nature found the resulting drug, lugdunin', could treat MRSA infection. The researchers, at the University

of Tubingen in Germany, say the human body is an untapped source of new drugs.

The last new class of the drugs to reach patients was discovered in the 1980s.

Nearly all antibiotics were discovered in soil bacteria, but the University of

Tubingen research team turned to the battlefield, to put on a microscopic level

a struggle. This space for food is taking place between rival species of

bacteria. One of the weapons they have long

been suspected of using is antibiotics. Among the bugs that like to invade the

nose is Staphylococcus aureus, including the dreaded super-bug strain MRSA. It

is found in the noses of 30% of people. About 30% of humans carry this

Staphylococcus.

Tests reported in the Journal of Nature found the resulting drug, lugdunin', could treat MRSA infection. The researchers, at the University

of Tubingen in Germany, say the human body is an untapped source of new drugs.

The last new class of the drugs to reach patients was discovered in the 1980s.

Nearly all antibiotics were discovered in soil bacteria, but the University of

Tubingen research team turned to the battlefield, to put on a microscopic level

a struggle. This space for food is taking place between rival species of

bacteria. One of the weapons they have long

been suspected of using is antibiotics. Among the bugs that like to invade the

nose is Staphylococcus aureus, including the dreaded super-bug strain MRSA. It

is found in the noses of 30% of people. About 30% of humans carry this

Staphylococcus.

The scientists discovered that

people with the rival bug Staphylococcus lugdunensis in their nostrils were

less likely to have Sinus. The German team used various strains of

genetically-modified S. lugdunensis to work out the crucial piece of genetic

code that allowed it to win the fight to live. where they eventually pinpointed a single

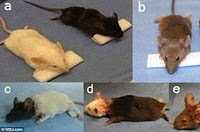

instructions for building a new antibiotic,Tests on mice showed lugdunin could

treat superbug infections on the skin including MRSA, as well as Enterococcus.

One of the researchers, Dr Bernhard Krismer, said: "Some of the animals

were completely clear, no single cell of the. "Others were reduced lugdunensis could reach patients and it may not prove. But new antibiotics are

desperately needed as doctors face the growing challenge of infections that

resist current drugs and could become untreatable.

'Pressure to eliminate' all the known causes of pathogens Fellow researcher Prof Andreas

Peschel said the body could be mined for new antibiotics."Lugdunin may be

the first example of such an antibiotic, we have started a screening

program," he said and he even believes that people could one day be

infected with genetically-modified bacteria to fight their infections. He argued: "By introducing the

lugdunin genes into a completely innocuous bacterial species we hope to develop

a new preventive concept of antibiotics that can eradicate pathogens."

Prof Kim Lewis and Dr Philip Strandwitz, from the antimicrobial discovery

centre at Northeastern University in the US, commented "It may seem

surprising that a member of the human microbiota - the community of bacteria

that inhabits the body - produces an antibiotic.

"However, the microbiota is

composed of more than a thousand species, many of which compete for space and

nutrients, and the selective pressure to eliminate bacterial neighbours is

high." Prof Colin Garner, the head of Antibiotic Research UK, told the

BBC: "Altering the balance of bacteria in our bodies through the

production of natural antibiotics could eventually be exploited to fight off

bacterial infections."It is possible that this

report will be the first of many demonstrating that bacteria in our bodies can

produce novel antibiotics with new chemical structures. "Alongside a

report that men with beards have fewer pathogens including MRSA on their faces

than clean-shaven men, it seems the paper identifying lugdunin should be viewed

alongside facial hair as a preventer of infection."